How shall any tower withstand such numbers and such reckless hate?

-Theoden, King of Rohan

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, though doing so is understandable in the current existential hellscape, you likely know that there is a new edition of D&D. Editions of D&D come in two varieties: revolutions and revisions. Both types come with perils and promises.

Revolutions are more prominent and typically slightly better received. They’re a wholesale rethinking of the game to focus on updated gameplay. AD&D (1st Edition), 3e D&D, 4e D&D, and 5e D&D are all revolutionary editions. The first was an utter expansion and reorganization of the original D&D (often called OD&D), the second a generation rethinking of AD&D and D&D, the third a rethinking of 3e, and the last a rethinking of both 3e and 4e.

Revisions are mostly reorganizations and sometimes an expansion of the game. They include the BECMI edition (culminating in the D&D Rules Cyclopedia, 2nd Edition AD&D, the 3.5 D&D, D&D Essentials, and D&D 5e (2024). Revisions keep the core of the old game, sometimes even slavishly so. At best, they clarify and, through that clarity, can often expand their audience. Often, they make tweaks to the rules systems for better playability. At worst, they bend to weird social pressures, hoping to erase some perceived past sin.

The second edition of AD&D is a perfect example of all these. The game’s first edition was a brilliant anomaly, primarily spearheaded by the gumption and imagination of one man, E. Gary Gygax. It was a brilliant and entertaining game entirely shaped by the eclectic mind of that man and his closest confidants, and it shows. Often, it was nearly a stream-of-consciousness rant piggybacking on a host of heroic fantasy and wargaming culture jargon and concepts. Both were the most obscure of subcultures at the time of the game’s development and release. It had more boobies. It had a bad habit of treating women and other cultures with a laugh up the sleeve. In other words, while a revolutionary new way to look at games and even fantasy, it was steeped in the 70s and 80s culture. But anyone well versed in those decades will notice that very few of the game’s criticisms came from that direction. But we’ll get to that in a bit.

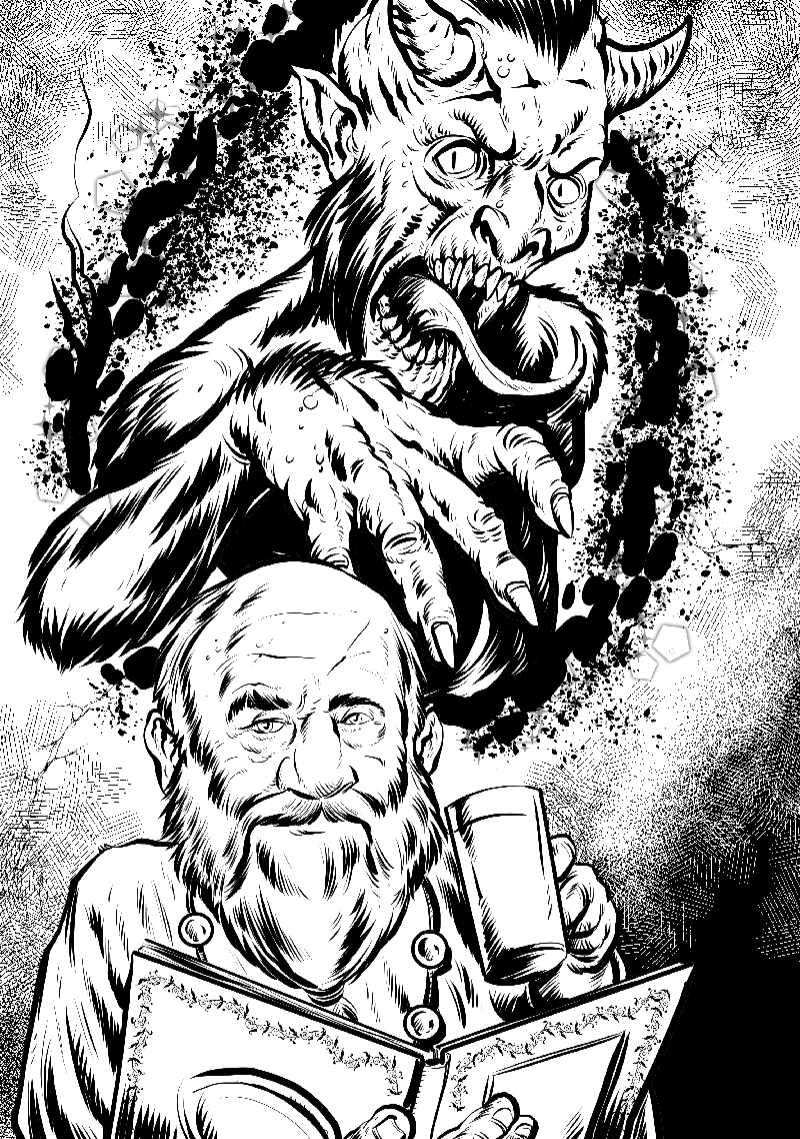

This edition, in many ways, is a breath of fresh air. Zeb Cook and Steve Winter (among others at TSR) pushed the game’s prose into a clarity grinder, scrubbing out bits of Gygaxian garble (though sometimes, debatably, its “charm”) and often trimmed it off its weird bits of chauvinism and the occasional esoterism and cultural gaffes. At the same time, it was entirely a product of the Satanic Panic. And scrubbed out references to what was seen as problematic to fundamentalist and holy-than-though pearl-clutchers, like assassins, demons, and devils, and playing bad guys. Of course, in a game that is predicated on heroes beating the shit out of bad guys (and taking their stuff), demons and devils would eventually return, rebranded with nearly unpronounceable names. They were just too good of bad guys to let sitting on the cutting room floor. By then, the damage was done. The cardinal rule of sandbox games like D&D is, “Thou shall not take away toys, especially at the whim of questionable assertions.”

The new edition / not an edition of D&D (like 3.5 or Essentials), is like 2nd Edition in weird ways. The general structure of the game is unchanged. If you know how to play 5e, the good news is that you don’t have to relearn any of the basic rules or the structure. It’s the same, except for where it’s not. The new books are beautiful and well organized, though the Monster Manual is a morass of misguided categories in more ways than one, and they are bigger! Boy gamers like bigger! Mostly. Like 2nd Edition AD&D, it’s more precise when describing and organizing the game’s terms and procedures, at the price of toys and charm.

There have been countless YouTube and TikTok hours of griping about orcs. There is hair pulling and gnashing of teeth while wondering why this change was necessary. Strangely enough, if you follow the breadcrumbs, this phenomenon is multifaceted and a long time coming. But that doesn’t mean it is necessary. Let me explain.

Orc is an old word. It appears in Beowulf (as a plural compound orcneas) as a monstrous tribe belonging to the descendants of Cain, alongside elves and ettins (giants), as creatures condemned by the Christian god. It probably originates in the Latin orcus (the underworld) and is closely related to the English word ogre. Its use in Anglo-Saxon is where Tolkien picked it up, using it first as an Elvish name (a sword called Orcrist, the Goblin-cleaver) in The Hobbit and then as an often-used alternative name for goblins in the Lord of the Rings.

Undoubtedly, the orcs that appeared in Chainmail and OD&D are Tolkien’s orcs. Early printings of OD&D suggest this. In the Fantasy Supplement of the former rules, they are described as “nothing more than overgrown Goblins.” A close read of Chainmail will pick out a rather broad goblins family tree. There are goblins themselves, kobolds, hobgoblins, and orcs.

Then came the litigation. Not only were several names used in Tolkien’s work sprinkled throughout Chainmail and OD&D, but TSR had purchased a board wargame by Larry Smith, publishing their version in 1975. That caught the ire of Elan Merchandising, who had a license with the Tolkien Estate, and they sent TSR a cease and desist, thus shelving the Smith game and leading to scrubbing of the terms balrog, ents, hobbits, and wargs from Chainmail and OD&D.

The next time we see the orc in D&D, it has a pig-snout makeover, which Gygax later claims was a miscommunication from the artist. However, it’s reasonable to assume that this was somewhat embraced to cleave apart D&D orcs from Tolkien orcs. Gygax let spewed much breath and typewriter clacks later, denying the influence of Tolkien’s work on D&D, often unconvincingly.

And these orcs were no longer the kin of goblins and hobgoblins (except for the weird fact that they could breed with anything except for elves), but their competitors. Other games and intellectual properties would make their mark on orcs (orks). Games Workshop lost the pig face, and made their green, tusked orcs a band of blissfully idiotic killers. Blizzard swiped GW’s orc aesthetic, eventually making them a new form of fantasy Klingon. This leads to a mishmash of precisely what an orc is among geek and even popular culture.

Much like the Klingons, what was first designed as a foe to be thwarted became a beloved archetype of the noble outcast among us—a Last of the Mohicans in reverse. This was a potent trope, especially in the late 1980s. Nasir from Robin of Sherwood, Worf on Star Trek: The Next Generation, and Drizzt from the Forgotten Realms novels all spearheaded a trope arguably finding a somewhat messy, modern genesis in Louis from Interview with the Vampire. It’s a weird story of redemption, but only on a case-by-case basis. Its popularity, or the popularity of haunted antiheroes is no mystery, especially among a fanbase of dissatisfied freaks and geeks shackled to suburbia. You might as well ask why so many 80s nerds love Rush, and why Tom Sawyer and Subdivisions sit at the top of their hits chart.

With this trope as a foot in the door, some folks started questioning the seeming essentialism, often intrinsic to Dungeons & Dragons. The game’s alignment scheme does it no favors. It’s often read as some Neoplatonist shithole bathing it recipient with the forms (but not the functions) of morality. It’s an astrology or Myers-Briggs test for nerds, and just as valuable. That was never the case, even in the first description of the simplified Chainmail or OD&D law-chaos alignment system, which states: “It is impossible to draw a distinct line between “good” and “evil” fantastic figure. Three categories are listed below as a general guide for wargamer designating orders of battle involving fantastic creatures.” Alignment has always been about tendencies rather than essences. On top of this, the realization that the grand majority of fantasy pillages myth, history, archeology, and anthropology in constructing its milieus, had some folks stumbling toward creating moral metaphysics about creative works. A new version of Christian thought policing—that somehow if you imagine, write, or portray an injustice or crime, you are guilty of that injustice. Suddenly, the only thing wrong with orcs was that they were the “other,” and that’s racist. The argument has a little more subtlety (or convolution) than that, but in essence it’s coming to the defense of invented entities though hypothetical connections to injustices perpetrated on real people, usually with little or trumped up evidence for the supposition.

Of course, the Monster Manual has more than a handful of intelligent, human-shaped folk other than orcs. What are their fates in this strange exercise? A handful of them with the humanoid type are in the same boat as orcs. As for other, Wizards changed their creature types. Once kin to orcs, goblins, and hobgoblins are now fey (though somehow elves aren’t…go figure), and kobolds are dragons. And that’s okay, because the “sin” of demonizing the “other” is just wiped away when you make them more “other” than before, I guess.

But none of this is okay. It reeks of boardroom or message board philosophizing, where the person who moped or yelled got their way. I’m sure the architects saw these changes as a revolution. A feature rather than a bug, but in the end, it’ll be a failed and ignored revision. Put it in the dustbin of getting rid of demons and devils and lauding a version of magic missile that doesn’t auto hit. Congratulations, you broke that cardinal rule.

I want to say that all of us know that racism, sexism, homophobia, and other forms of bigotry are wrong. But today, it seems the juveniles have taken over, and folks are crawling back to believing they are somehow funny or “common sense.” Bucking a near-century trend, I’m not interested in proxy wars or abstract ideologies from some emotionally self-righteous ponderings. The real fight is ongoing in the real world. Winning those fights is critical. Patting oneself on the back for liberating make-believe people from make-believe forms of problematic whatever by shuffling or veiling categories doesn’t cut the mustard. It doesn’t even look at it askance. This old chestnut shares a type awash with the same bullshit that bolstered the PMRC, BADD, the Comic Code, as well as thousands of lunatics on social media: that somehow, evils perpetrated by evil characters in fiction or play are the reason that people make truly shitty decisions and then act upon them. It’s a story as old as Plato’s Republic and as substantial as Atlantis. I am sorry to those still holding their breath for that canard. Art and fiction may be magical, but it isn’t black magic. Loneliness, hatred, poverty, tyranny, sickness, and ignorance are sufficient and far more potent in their malevolence. Instead, this shares same category of absurdity that bans books for being too queer or too “woke” or by idiots who do most of their thinking on the toilet or believe that meditation and yoga will let the devils in—utter nonsense. This time it has just U-turned in a different flavor of absurd social agenda.

Luckily for all of us, tabletop roleplaying games are simple to hack. You say, “I pretend differently.” Given some early indicators of how the 5e 2024 edition is doing, people already are.

Leave a Reply